Given the dominance of the Republican party, most of Oklahoma’s elections in November 2026 will effectively be determined in the closed Republican primaries in June and any runoff primaries in August. While over half of our registered voters are now Republican, most of them don’t actually vote in the elections that truly count. I anticipate that perhaps 1/3 of registered voters, or perhaps 1/7 of the state’s voting age population, could determine most statewide elected offices, along with six out of seven seats in Congress, months before the general election.

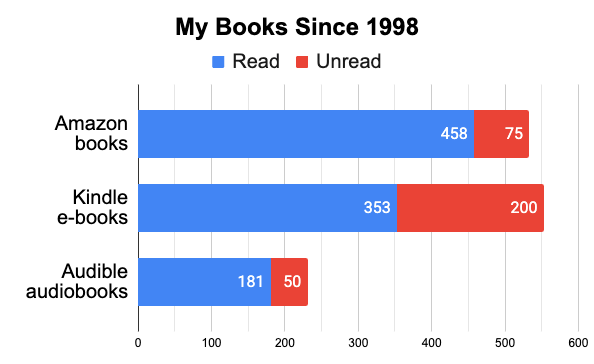

When I came of voting age in 1984, Oklahoma’s congressional delegation and state government were still dominated by Democrats. The OK Voter Portal shows that I voted in 67 elections in the 21st century, and I reckon that over the past 42 years I’ve been to polling places about 150 times. However, our general elections lost most of their competitiveness over 15 years ago.

As a student of Oklahoma’s history, I know that Democratic dominance in 20th century Oklahoma was boosted by both racism and populism. Bear in mind that Democrats were the Jim Crow party after the Civil War, in sharp contrast to the party’s racial politics after 1965.

At statehood in 1907, an influx of settlers from southern states reinforced the racism of slave-owning First Peoples who had been forcibly relocated to the area in the 19th century. The new state rapidly passed Jim Crow segregationist laws, including Senate Bill One, and the legislature enacted voting restrictions in 1910 and limited Black voting power until the mid-1960s.

Agrarian left-wing populism amongst working farmers and laborers also aligned with the Democratic party’s reform-minded, pro-labor, and anti-corporate platform. In 1907, the Oklahoma Constitution was longer than any of those adopted by the earlier 45 states. It was drafted mostly by farmers, with some laborers and lawyers, presided over by the colorful and rabidly racist “Alfalfa Bill” Murray. It reflected Progressive Era ideals, direct democracy, and extensive business regulation with statutory-level details that would lead to over 150 voter-approved amendments by 2026.

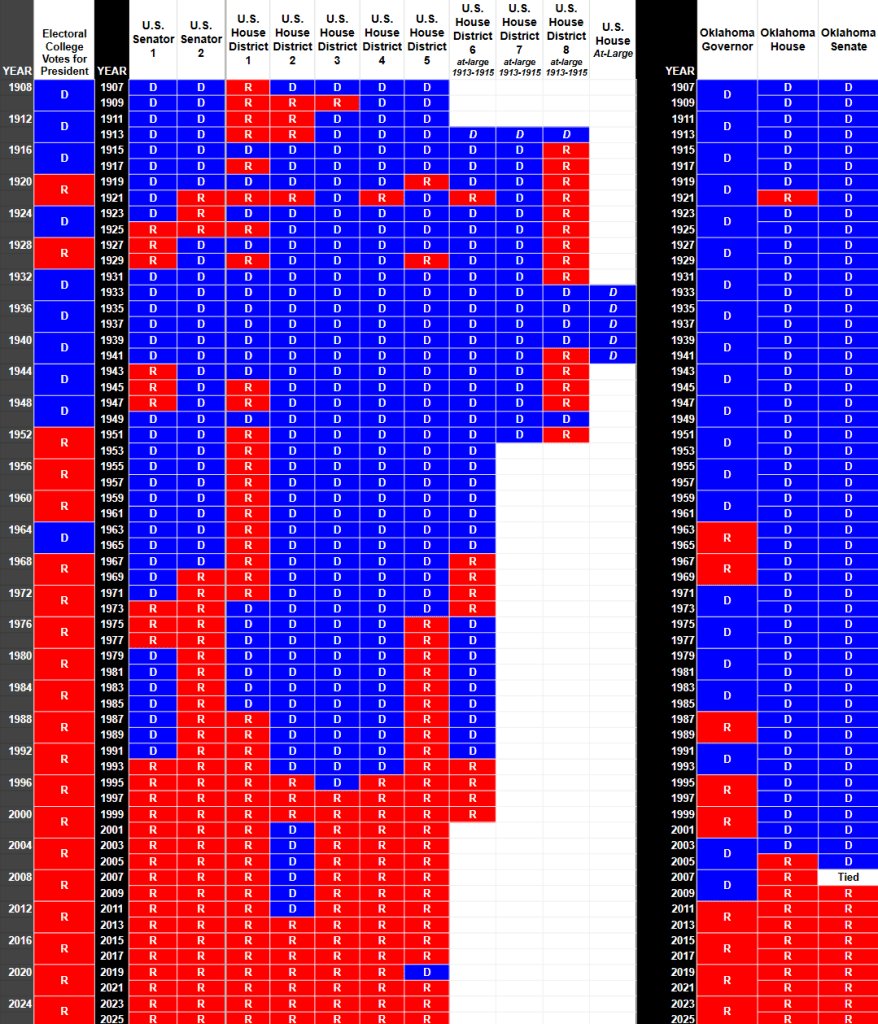

The Democratic party held 81% of the state’s legislative seats between 1907 and 1973, and its power was nearly absolute during most of the 1930s. A Republican did not win a gubernatorial election until 1963, and even then only 19% of Oklahoma voters registered as Republicans. However, Oklahoma’s conservatism also led it to give its Electoral College votes to Republican presidential candidates from 1952 onward, save for Lyndon Johnson in 1964.

Johnson’s support for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 triggered a white backlash that began to shift the state’s political alignment, with Republicans undertaking real efforts at organization statewide.

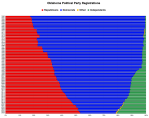

Oklahoma’s shift from Democratic to Republican control

Until the 1990s, most of the state’s delegation in the U.S. House of Representatives were still Democrats, but the realignment of Evangelical Christian voters toward the GOP allowed state Republican party chairs to target divisions between socially conservative Oklahoma voters and the national Democratic Party.

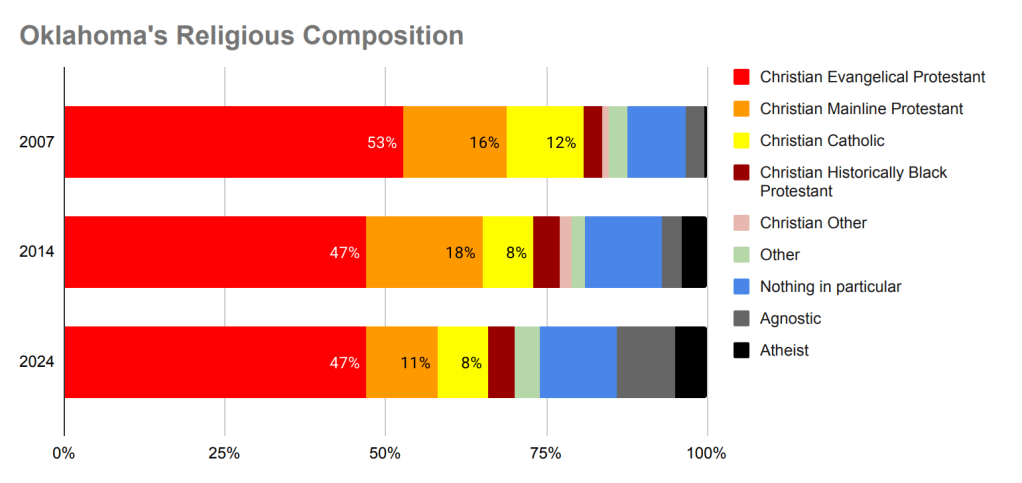

Conservatives now outnumber liberals by 2:1 in Oklahoma, and Evangelical Protestants dwarf all other religious groups. However, the increasing politicization of Christian churches has alienated conservatives from the aging and ever-shrinking mainline denominations while many moderates and liberals have fled Evangelical churches.

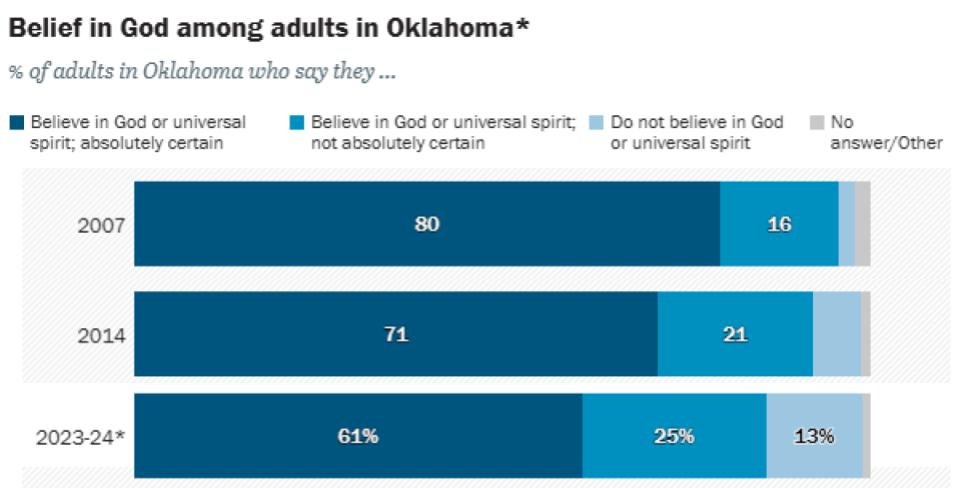

Oklahoma is still in the Bible Belt, but the religious composition chart also documents an increase in the religiously unaffiliated from 12% in 2007 to 26% in 2024, driven both by political alienation as well as an erosion of belief.

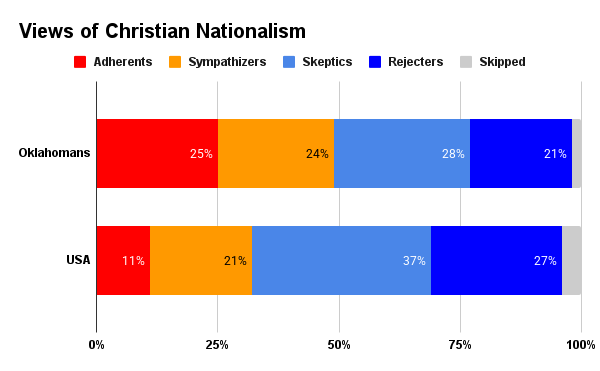

Oklahoma’s declining religiosity still leaves it with a huge block of Evangelical Protestants and thus a greater share of adherents and sympathizers of Christian Nationalism than all other states save Arkansas, Mississippi, and West Virginia.

Linking political power to religion inevitably leads to social repression and discrimination, and Oklahoma has witnessed increasing attacks upon and violations of the Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment, as evidenced by recent battles over state-funded religious schools, Islamic mosques, and reproductive rights.

GOP Dominance in the 21st Century

In the late 20th century there were still some healthy Democratic primaries for statewide offices. However, by 2010 the Republicans controlled the state legislature, governorship, and almost all statewide offices. Since 2020 the entire Congressional delegation has also been Republican. Donald Trump won every county in the state in the 2016, 2020, and 2024 presidential elections, whereas all other states had at least one county that favored the Democratic nominee.

Long-time pollster and election consultant Pat McFerron has noted how the 21st-century dominance of the Republican party in Oklahoma has led to most elections being decided by partisans in closed Republican primaries, with ever-increasing extremism. While Donald Trump dominated in Oklahoma’s 2024 general election, only 54% of Oklahoma’s voting eligible population cast ballots, which was the lowest turnout of any state.

Oklahoma is ranked 47th in political engagement with a lack of competitive races at the state level, disillusionment of young voters, and a general lack of motivation to vote. In June 2022, only 24% of registered voters participated in the Democratic and Republican gubernatorial primaries, and only 18% of registered voters participated in the March 2024 Republican, Democratic, and Libertarian primaries, even with Independents being allowed to vote in the Democratic primary that year, ensuring that every registered voter statewide was eligible to cast a ballot.

Just as Democratic dominance in the 20th century led to repeated corruption, now Oklahoma’s Republicans routinely create scandals such as the mismanagement of pandemic funding, mental health budget incompetence, and campaign finance violations. As Mark Twain dictated for his autobiography, “To lodge all power in one party and keep it there is to ensure bad government and the sure and gradual deterioration of the public morals.”

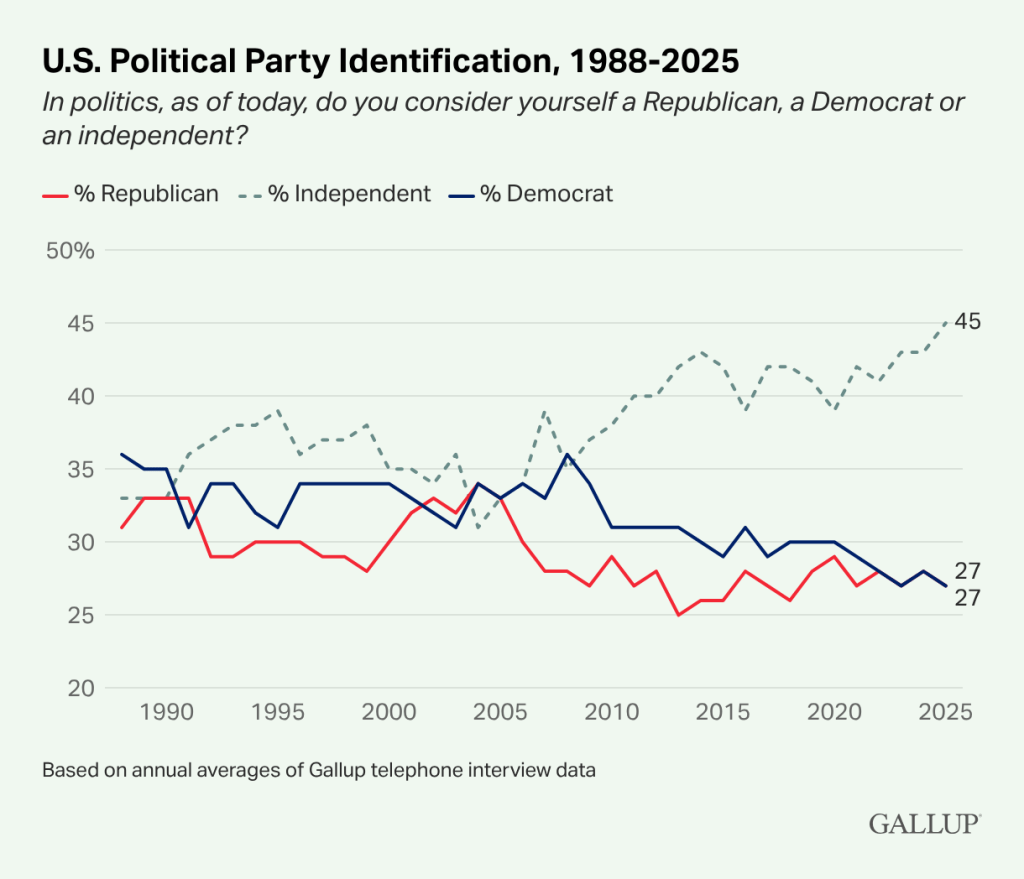

Independents

When I came of voting age, USA voters were fairly evenly split across Democrats, Republicans, and Independents. However, Independents drew sharply ahead of either party after 2008, driven by dissatisfaction with the handling of the Great Recession of 2008, disillusionment with the two-party system, and heightened political polarization.

A petition drive for State Question 836 aimed to eliminate Oklahoma’s closed primaries, but it failed to gather enough signatures to be scheduled for a vote of the people. Currently only Republicans can vote in their primaries, and while Democrats allowed Independents to participate in theirs from 2016 to 2025, their primaries will be closed in 2026 and 2027. The Independents who show up for the June 16, 2026 primary election will still have something to vote on, however, since Oklahoma’s conservative governor strategically scheduled State Question 832 on raising the minimum wage for the primary election date in order to suppress support for it.

Realpolitik says that, except in some metropolitan areas, Independents in Oklahoma who want their vote to count should register as Republicans and then vote in their closed primaries and primary runoffs. However, most people neither think nor act strategically.

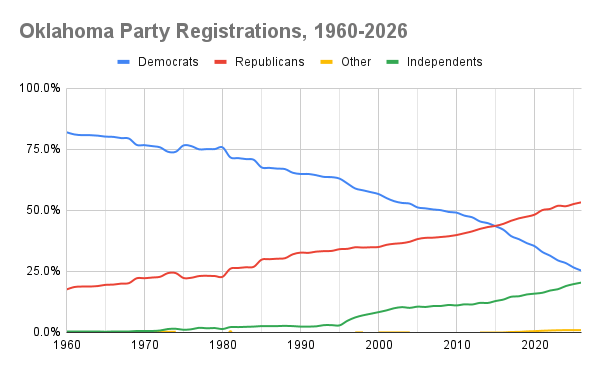

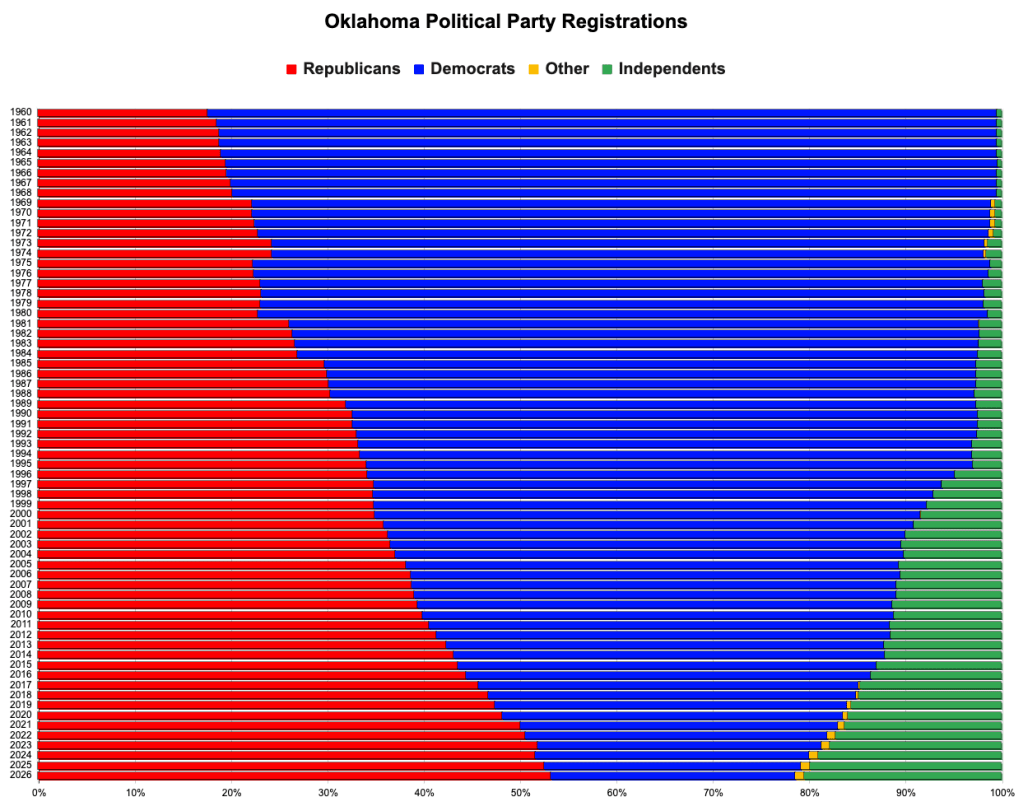

Consider Oklahoma’s party registrations from 1960 to 2026. Over that period, Democratic registrations fell from 82% to 25%, Republican ones grew from 18% to 53%, Libertarians grew to 1%, and Independents grew from 0.4% to 20%.

It has been interesting to see the party that long dominated Oklahoma politics steadily decline over my lifetime from 4/5 to 1/4 of registered voters, with Democrats only elected to the legislature from parts of the two metropolitan areas.

The Republicans outnumbered the Democrats after 2015, but the Independents are also coming on strong and in a few years could outnumber the Democrats, despite their registration ensuring they have little actual influence on which candidates are elected to office.

The partisan imbalance and low turnouts in the crucial primary contests have led to an Oklahoma legislature that is ever more extreme in its right-wing partisanship. That in turn has created friction when the more moderate electorate has opted to use initiative petitions to bypass the legislature in legalizing medical marijuana, expanding Medicaid, and converting low-level drug and property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors. Given the persistent trends, I expect that dissonance to continue to build for some time.